Next month, on Nov. 29, the Museum of History and Industry in Seattle will open an exhibit commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Battle in Seattle, a fin de siècle clash of global conscience and global commerce. Just prior, on Nov. 23, the curators will host a walking tour of the hotspots where a 40,000-person coalition of labor unionists, environmentalists, students, social justice advocates, and Indigenous activists met with tear gas and rubber bullets. The protesters demanded the World Trade Organization, then convening its third global trade summit, dismantle a form of globalism that, I agree, favors multinational corporations and wealthy nations at the expense of social justice, environmental sustainability, and democratic governance.

It was a defining moment for the anti-globalization movement, but the media’s portrayal of it as anti-profit and anti-business obscured deeper narratives of protecting global justice, environmental sustainability, and advocating for equitable global cooperation.

Today, the core concerns raised by those protesters remain unresolved. In many ways, the challenges faced by the global village have only worsened. The fiery call to dismantle globalism has given way to more pragmatic efforts to restructure it — which is also ineffective at marshaling the type of globalism we need to address a planet-scale climate crisis. I propose we look at it a different way.

The real economic carcinogen — whose current iteration began in 1972 — has metastasized into the dominant force shaping our world today: the financialization of pension funds. Let’s protest that.

You say globalism, I say carcinormalism

My collaborator

is right when he warns against “demonizing” globalism. We will never outrun the idea of one people on one planet, nor should we want to curb efforts to harmonize our global goodwill. While globalism is, by default, associated with economic systems and financial markets, it also represents a cultural, social, and technological integration that affects nearly every aspect of modern life.“We are trying to engage people in a new conversation about being human, together and apart, in society, through economy, using money, on a planetary scale, in the 21st Century, and beyond,” he says, referring to our Bank of Nature work. “That feels to me like globalism, in spades.”

The pain point is not globalism, but the financialization of the global economy. They sound the same but aren’t.

Financialization refers to the process by which financial markets, institutions, and motives dominate the economy, prioritizing short-term profits over sustainability and well-being. In today’s economy, the focus isn’t on direct investment in the real economy but on speculative markets, where financial instruments are traded for capital gains. Campaigns focussed on ESG and divestment, well intentioned, cater to this type of securitized economy, rather than counter it.

Behind this financialization lies a silent partner — trillion-dollar pension funds — used in ways that amplify the worst aspects of neoliberal wealth extraction, doing so at the expense of social justice, environmental sustainability, and democratic governance.

We’ve lived through the Gilded Age (the financialization of insurance) and the Roaring '20s (the financialization of personal savings). Today’s iteration is the financialization of pensions, which began 50 years ago by a perfect storm of tax changes, technology advances and a stunning relaxation of what it means to be lawfully “prudent”.

Eagle-eyed economists might point to the financialization of corporate debt (junk-bond Gekkoism of the 1980s) or the Subprimal Urges that financialized home mortgages leading to the crash of 2008. However, neither scheme could have existed, at least to the extremes they did, without the amplifying effect of financialized pension funds that defines “carcinormativity.”

Sidebar: The making of clever neologisms

A carcinogen is any substance or agent that can cause cancer by triggering abnormal cell growth. Environmentalist Edward Abbey, in The Journey Home: Some Words in Defense of the American West, captured this risk when he wrote, "Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell." Many interpret this as a powerful indictment of unchecked economic growth.

As a society, humans are constantly exposed to carcinogens. Tobacco smoke, asbestos, ultraviolet radiation, artificial sweeteners, alcohol, coffee (oops, not coffee) and human papillomavirus are examples. The list of known threats is long, but not as long as the risks that remain unknown. Often embedded in the fabric of daily life, carcinogens may be impossible to avoid. The common treatments are 1) to intervene with treatments that come with their own risks, or 2) to ignore the threat leading to further harm in the future.

Thus, carcinormalism refers to the process by which harmful practices become normalized, despite the clear, avoidable risks they pose. It’s also an entangled mess of other isms like profit maximalism (in contrast to generic capitalism), neoliberalism (characterized by deregulation, privatization, and free-market supremacy), consumerism, neocolonialism, narcissism and corporate gigantism.

Other words in the family:

Carcinorm: The toxic norm that arises from carcinormalism.

Carcify: To make something toxic or harmful.

Carcinomics: A toxic economic system driven by harmful practices.

Carcinogenism: The harmful financial practices that mimic the unchecked spread of cancerous growths within the economy.

Carcigentism: The perpetuation of harmful financial practices passed down through generations, like a hereditary condition.

Carcicapital: Harmful, toxic capital that destabilizes systems.

Carcinormativity: The expectation that toxic practices are standard.

Use at will.

A fiduciary reset

This "carcinorm" is what protesters stood against while being tear gassed in Seattle. The same silent partner that exacerbated the problems of global financialism in 1999 is still at work today — only now, financialized pensions are even more entrenched, profiting from extractive speculation when the real fiduciary focus should be, according to law, building a sustainable and dignified retirement future.

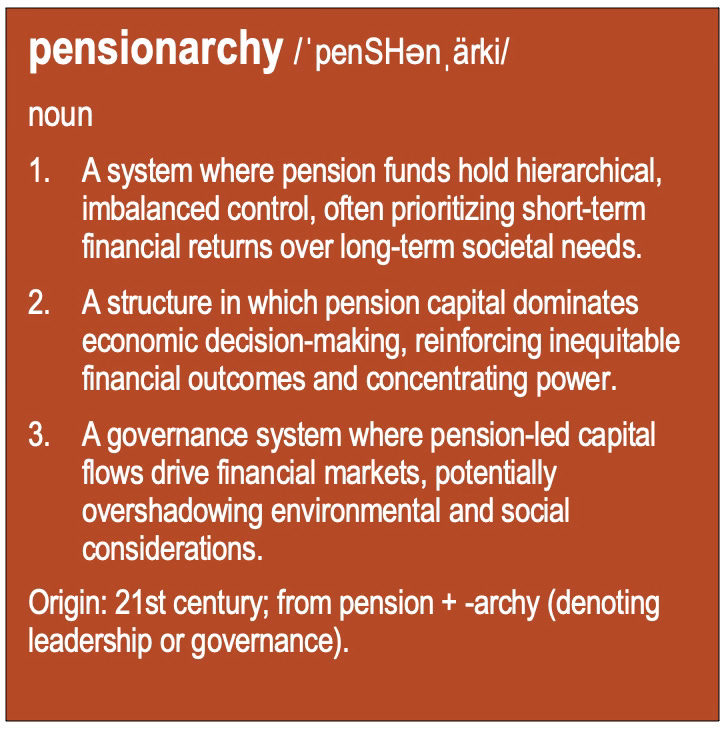

What we are witnessing and living is not just any form of globalism, but a toxic globalism driven by the pensionarchy of the economy — where pensions, originally designed to provide security for retirees, now bankroll short-term speculative gains and amplify financial risk. A system once meant to protect has turned deadly, contributing to instability and exploitation.

An avoidable disease often comes with a cliché: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” It points to the multiplier effect of prudence.

When it comes to addressing carcinogenism in our fiduciary systems, a trillion-dollar prevention of anti-future investments could multiply into a planet of cure.

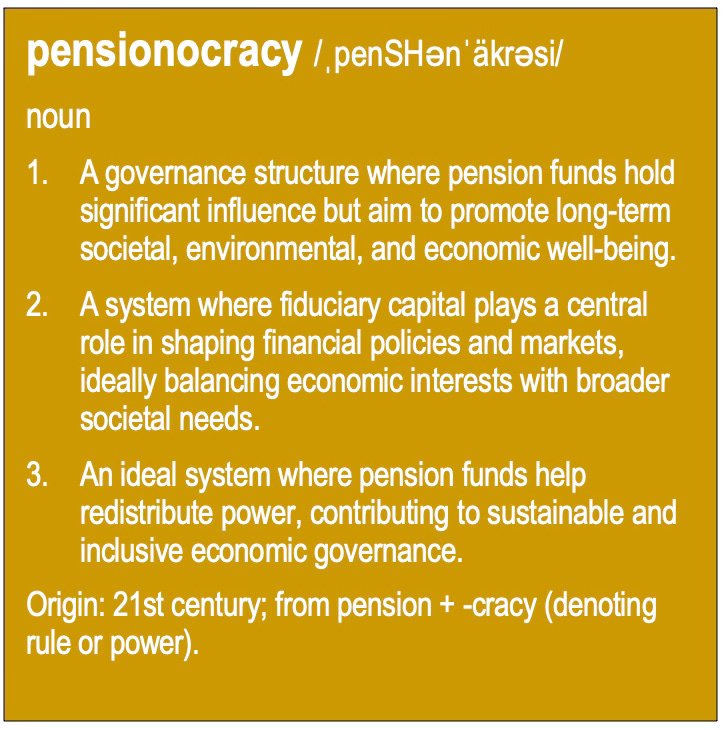

This fiduciary reset is a strategy to bring pension funds back to their original purpose: protecting future retirees through loyalty, care, and impartiality. As fiduciary assets are equivalent to 35% of global GDP, reallocating $35 trillion from carbon-enabling investments to social and environmental protections could be the planet-sized cure we need. Let’s call it a pensionocracy.

That’s our work — which, even for fervent anti-globalists, seems “audacious in the extreme” at a time when, as a terminal patient, we might be more accepting of non-traditional medicines.

Innovation will be the sweetener that makes this fiduciary realignment more tolerable for those clinging to the status quo. By embracing new financial models, impact investing, and social enterprise as core elements of the fiduciary mandate, we can demonstrate how fiduciary compliance not only meets long-term financial goals but also ensures a sustainable and just future.

This isn’t about tearing down the existing financial system, but rather evolving it —transforming it into something that fosters both economic prosperity and habitat longevity, making the system truly healthy.

This spoonful of innovation offers a compelling vision: pension funds realigned to support climate stability, social justice, and a fairer economy — a vision of fiduciary globalism, where future retirees (and the rest of us, riding coattails) can thrive in a world that’s no longer at war with its own ecosystems.

Death by indifference

Until then, the World Health Organization says climate change causes 150,000 deaths per year due to extreme weather events, disease, and food shortages (250,000 per year by 2030). People are killed by economic indifference to the social and environmental cost of profit. There is nothing wrong with trying to make margins that pay for wages, housing, education and groceries. That’s why we talk about actuarially-defined sufficiency growth. That’s the rate of increase that allows society to feed, eventually, 10 billion people living in a world of climate security — or a far-better approximation of security.

Governments face this trade off — choosing economy over public health leading to unintentional deaths. Corporations can justify unintentional deaths as a cost of protecting shareholder value.

Pension funds, though, don’t have the same luxury to trade life for ROI. They are “both, and” versus “either/or” and rhetoric that their job is to maximize risk-adjusted returns regardless of the damage that ROI causes is inconsistent with the protections owed to their own pension participants. For example, by enabling fossil fuel company impacts on climate and ignoring the related health risks, pensions are failing a core function that distinguishes them from other actors, making their complicity a matter of fiduciary failure rather than simply economic calculus.

The unique role of fiduciary funds — spanning national boundaries and investing with minimal restriction — echoes many of the broader characteristics of global finance, but they also carry their own set of unmet implications for the global economy. Presently, that’s paying for carcinomics made deadlier by money that is supposed to sustain a long and healthy life, but doesn't.

Hindsight is 2024

If the protesters from the 1999 Battle of Seattle were to host a reunion next month, they would have an incredible opportunity to reframe the protest in a way that addresses the real issues with more clarity, focus on viable solutions, and actionable steps in today's context.

Shift from anti-globalism to pro-global village

Reignite the power of organized labor in the global economy

Evolve to environmental sustainability to planetary stewardship

Present a vision for a post-neoliberal global economy

Point attention to decarcifying carcinormalism.

For the record, I don’t have a plan to rally in Seattle, but if any organizers out there want some ideas, I’m happy to arrange a call. Don’t reunions give us all a chance to look back objectively to assess, lament, repair and identify that invisible drivers of past choices? Is hindsight 2024?

What great knowledge this group has on how the system currently operates and where the leverage points are to transition to a thriving world, for retirees and all of us.

It appears that the pension fund managers need other feedback and a broader context in order to perceive that their current investment strategy is causing harm in the near term, and potential devastation in the long term.

“ This isn’t about tearing down the existing financial system, but rather evolving it ”

The evolution we need begins with the fiduciary duty of pension trust fiduciaries to exercise the care, skill, prudence and diligence, under the circumstances then prevailing, of the prudent person familiar with such matters, acting in like capacity, of like character, with like aims.

There is a lot to unpack in that densely concise rule of law, but we can start with capacity: what powers do pension trustees derive from the character of the trust over which they exercise plenary authority, constrained only by fiduciary duties of prudence (see above) and undivided loyalty to the aims of the trust over which they exercise sole and exclusive control?

(A back-to-the-text restatement of the pension promise, and how that promise is provisioned by a social trust as a public good for a private benefit that is also a public good, is in order. But not here.)

Let’s look at the increasingly popular innovation coming out of the Asset Ownership view of the capacity of a pension fiduciary (as created by the character of the pension trust over which they exercise sole and exclusive control, constrained only by fiduciary duties of caring as prudent person familiar with such matters, and undivided loyalty to its chartered aims): Private Equity.

Private Equity uses financial engineering for value creation.

Financial engineering is when you use the technologies of spreadsheet math, desktop publishing and digital communication to negotiate the design of an enterprise: it’s core technology (suitability to the times); it’s social contract with popular choice (longevity over time); the protocols for how the business will do business (fairness all the time).

Value creation is highest possible purely pecuniary profit extraction maximization, through leverage (borrowing to pay fees and dividends) and as gain on sale to a buyer in the capital markets (the ultimate exit that shifts the risk onto some else [slice-and-dice before we pump-and-dump this "hot potato"), solely in the financial best interests of Private Equity.

Value creation through financial engineering for extraction maximization by Private Equity is only possible because of pensions (see Peter Drucker, Harvard Business Review 1991)

This indicates that the capacity of a pension fiduciary includes the power of financial engineering through negotiated agreements with enterprise, directly.

Why can't pension fiduciaries exercise that capacity directly, rather than only delegating it to Private Equity (that has a different aim [to maximize their own profits, through extraction] than a pension trust [to assure security and dignity to workers, directly, and to us all, consequently, through interaction]).

This is the transformational innovation in social choosing that we need for being human in society, through economy, using money on a planetary scale in the 21st Century, and beyond: where Private Equity engineers to maximize its own fees and profits through extraction, pension fiduciaries have the duty to engineer for their chartered aims, which are to invest money for income as well as safety to assure income security in a dignified retirement for evergreen populations of current and future retired workers, through interaction.

When pension fiduciaries do their duty to assure security and dignity to workers, as a private benefit, directly, they also, of necessity, deliver security and dignity to us all, as a public good, consequently.

This is because the sums of money aggregated for the benefit of so many workers, collectively, worldwide, are so large, that it is not possible to deliver security and dignity to so many, at such scale, directly, without also delivering security and dignity to us all, consequently.

Pensions are, de facto, a proxy for the public good.

As a stewards of a social trust for a private benefit that is also a public good, pension fiduciaries have to be accountable to the public’s sense of what makes sense as a prudent person.

Are you a prudent person?

If so, you have a say.

Which do you choose?

The status quo of extraction?

Or, the 21st Century modern innovation of interaction?