Unless her felony convictions precluded her from the job, Goldilocks would have made a fine defined-benefit pension fiduciary.

She had a rare talent.

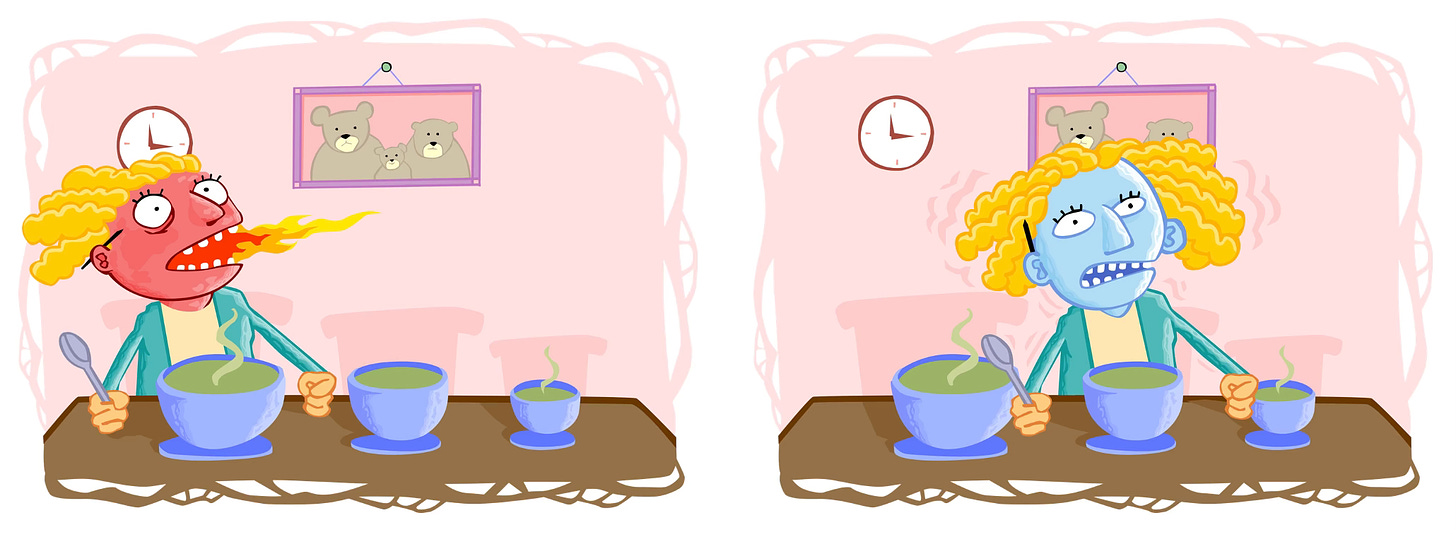

She had the ability to synthesize myriad quantitative and qualitative data points into a reasoned "just right" conclusion, navigating between the polarizing extremes of too hot and too cold. That she was shrewd, sagacious, perspicacious and, astute — all the qualities of prudence — is only evident after she made the imprudent choice for which she’s remembered.

She joins the ranks of other social scientist savants who worried little about how they discovered their breakthroughs. Like psychologist Cyril Burt, whose influential work on intelligence and heredity was overshadowed by accusations of fudging research numbers, or sexologist Alfred Kinsey, who may or may not have participated in his own data collection, Goldilocks' discovery of a Just Right Index is warped by a focus on her questionable field research methods. As we know, these methods include breaking and entering, porridge theft, and property damage.

For this unorthodox approach, and regardless the gift she left humanity, she was disappeared… never to be heard from after she ran into the wood. That’s the terrifying moral we tell children to ensure their compliance with accepted norms that are, too often, just wrong.

Goldilocks’ Just Right index (or Goldilocks Effect) is a critical thinking tool to ascertain a reasonable happy medium — otherwise known as fiduciary-grade common sense — between two or more extremes.

It is especially helpful in deciding what common sense is when it must also encompasses the various fluid factors reflective of time and place. What is reasonable today is not what was reasonable yesterday due to technologies, priorities, and any other “new zeitgeists” for decision-making.

For example, Fiduciary Goldilocks would have a lot to say about whether, and to what extent, core human-scale qualities comprising fiduciary reasonableness are “too out of whack” or “just whack enough”.

Loyalty is a rich category of faithfulness that extends to the fidelity, allegiance, fealty, devotion, and even piety that we pay to a pledge, obligation, duty or trust.

Care. Do we give zero cares about care? Supervision, watchful attention, conscientiousness, carefulness… even scrupulousness… comprise a meticulous understanding of care.

Impartiality is the big word for fair, just, equitable, unbiased, dispassionate, and objective that means free from favor toward either or any side. Nonpartisan.

As we scan global human society, have we lost sight of what are reasonable common sense standards of loyalty, compassion and fairness made — rather like porridge — too hot or too cold?

The degree to which the rest of the world agrees is a Just Right Index question. And, more importantly, it informs how we engage with the specific legal standards that define loyalty, care and impartiality so that we should know in law if and when we have breached our contracted minimums.

I hope you’ll answer three questions. I’m playing with the Substack polling feature to survey our nearly 1,000 readers and their networks. If you share this post link with your people and encourage them (wink, nudge) to subscribe, we can get a just righter sample size.

I’ll make the tallies public as we get to a “reasonable” sample of respondents. Thank you for helping us measure what fiduciaries are navigating in a real-society context. Please share, comment, subscribe and or like as appropriate.

The question about loyalty needs further refinement. I suspect that most people would profess loyalty to someone or something. It may be to an institution, an idea or dogma, a person and maybe not a good person.

So then, is loyalty per se a good thing?