Introducing "fiduciary-grade" investments

An opportunity for climate finance, pension fiduciaries and future beneficiaries

A Feb 2024 update: This bill was recommended for “study” for the joint committee reviewing it. That means it’s in a limbo until we refile a new version in January 2025

A fair question in the analysis of the newly renumbered fiduciary standards senate bill S.1644 (formerly bill SD2252) is:

"What happens to the money in a pension plan portfolio

that fails a fiduciary review?"

For example, in Massachusetts, a 10% failure of the current portfolio means $9 billion needs to be reinvested. Where does it go? This is a good problem that opens the door to how really big money can address really big challenges when other public money can’t or won’t.

Where does it go?

There is the non fiduciary status quo answer dedicated “solely” to growth that says it goes nowhere. It stays put.

Those fiduciaries say, without the exhaustive research and studies to prove it, that “There is no alternative” to the current use of speculative markets, oil and gas investments, and other extractive economics that have already damaged the now and continue to damage the future.

For illustration, Stand.Earth reports that the Massachusetts Pension Reserves Investment Trust has $2.6 billion in fossil fuel investments — or about 3% of its overall holdings — despite an active divestment-activist movement that wants that money to do better for the long-term environment.

There is the fiduciary-compliant stewardship answer imbedded in the existing law, but is made explicit in the bill.

Those fiduciaries say “Somewhere we haven’t looked before”. We call that the “Untaken Safer Alternative Path.” Stewardship money is dedicated “solely” to managing the Pension Promise for all beneficiaries now or decades from now when they are age-eligible to collect. Delivering the Pension Promise involves quantitative and qualitative considerations — which is the full and legal meaning of fiduciary duty that is unmet in ubiquitous modern practice focussed on growth at all costs.

Really REALLY big money

The answer to “Where does compliant money go?” matters because of the behemoth scale of money in play. Depending on the public pension, it’s billions and maybe trillions that are used to fulfill specific duty that has arguable terms and conditions that must be met over the long term.

A 10% failure adds up to $9B in MA, but $200B in California and $2.6 trillion, with a T, globally. That scale of misapplied money touches everything and everyone, beneficiary and non beneficiary, and has a dominant place in any economy.

That means we need a category of investment that is tailor-made for fiduciaries…. a “fiduciary-grade” investment that checks all the boxes, including a minimum rate of return.

What if a 10% failure rate from fiduciary review were conservative?

Let’s pare back the mechanics of a public pension plan

that must fulfill a specific duty.

#1 A fiduciary must make a return on investments.

Whether that’s to protect the obligation to current retirees owed regular checks or to protect the ability to meet the obligation decades from now, that’s a given in the bill and does not change. So, in MA, $90B must move through the market to earn a minimum rate of return that supports the value of the fund for retirees to get their “owed” regular financial support, plus administration costs and fees paid to third-party asset managers.

Depending on the pension plan, required ROI is maybe 7% +/-. It’s a target set by an actuary professional who evaluates the long-term financial health of a fund, risks and what has to be earned today to maintain that financial health.

So, in MA, $90B should return about $6.3B in interest, dividends and other revenue from investments each year. It’s worth noting that PRIM in Massachusetts in 2022 actually lost 10%, down from $101B in 2021.

If growth is the sole interest of a public pension fiduciary, is a 10% loss year-over-year a fiduciary breach?

#2 A fiduciary must protect a fund beyond their lifetime or career.

Public pension plans in MA are already 112 year old and the same plans are obligated to pay benefits for as long as the youngest beneficiary is eligible to collect. We say that’s a 75-year window of obligation the rolls forward with every new hire.

As of this writing, a 75-year window extends to 2098 — so mere mortals who are managing today’s fund have a legal responsibility to beneficiaries who will outlive them and outlive current retirees. Best practice in global pension funds today forgets this obligation to the future — which is a clear breach of fiduciary duty.

#3 Taxpayers guarantee the delivery of benefits.

A public pension fund — whether it’s in good financial health or “underfunded” and in bad financial health — has a backstop that ensures that eligible pension beneficiaries will get their benefits no matter what.

The US Supreme Court, in the 2020 decision Thole v. US Bank, made clear that taxpayers make up any shortfall, should a public pension struggle to provide the owed pension benefits. If underfunded positions are guaranteed, then there is no risk of damage suffered by the pension beneficiaries.

Whether it was intended this way or not, the Supreme Court ruling means the taxpayer is a vested interest in how the fund operates and why. Our bill explicitly identifies the taxpayer as a beneficiary of the pension fund, not just because of the guarantor status but because the pension fund stabilizes and protects older people in a way that protects the economy and society as a public good.

It’s not IF that money needs to be prudently invested,

but HOW that money is prudently invested

The bill argues that the sole interest of fiduciary duty is to protect the pension promise, which supersedes any need for growth. Growth for the sake of maximized growth -- regardless of the long-term damage of that growth -- is non-fiduciary.

Instead, the bill argues that a fiduciary must earn a sufficient cash flow return from enterprise that protects the future. That's how the bill defines the quantitative and qualitative requirements of the sole interest of protecting the pension promise over the next decades.

The bill calls that a "Fiduciary-Grade Investment”.

The bill defines fiduciary-grade investment as an investment of fiduciary money, like a public pension plan, that generates fiduciary minimum returns, such as cash flows, that reckon with negative externalities those returns accrue to the future. As far as we can tell, there is no such thing as a fiduciary-grade investment — yet.

Therein is the opportunity to consider how billions in fiduciary money might be otherwise spent to meet the restated definition of fiduciary duty. This is where fiduciaries can get creative with their legal obligations to “steward the future” -- because their duty makes them look at distinctly different alternatives than what the status quo presently offers.

What's a good example?

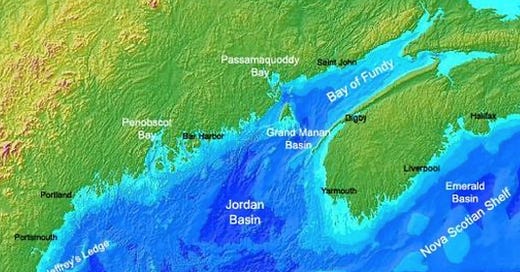

The Biden White House has identified the Gulf of Maine energy basin as a priority in the "just" energy transition from oil and gas. This is a multi-state and multinational opportunity. It’s very early stage, despite being a good idea for decades. It needs development and execution at the scale of capital already available at the many public pensions in the region.

Pensions could make this happen right now. An alliance of public pensions could fund the Gulf of Maine project as a utility that produces a minimum rate of return over the decades. This is the scale of investment that is equal to the scale of public pension funds — especially those that collaborate on fiduciary-grade investments.

At Bank of Nature, fiduciary-grade investments will be our offering to investors.

How do pension fiduciaries

use their enormous financial scale to do better?

Money talks and a “Duty to Negotiate” (as is included in the bill) is the explicit fiduciary duty to acknowledge the purchasing power of public pensions to negotiate with fiduciary-grade enterprises better terms that meet fiduciary values.

This is part of our ongoing discussion, but to be a fiduciary-grade investment, the enterprise might meet this checklist:

Longevity in terms of the decades-long social contract required of public pensions

Sufficiency of cash flows that make good on ROI, administration costs and fees.

Fair trade in all supply chains

Fair engagement with law and community

Fair reckoning with the consequences of business activities on nature and society, now and in the future

Fair working conditions and compensation

Fair dealing with customers and competitors in all distribution channels

Fair sharing between the enterprising visionaries and their financiers,

fiduciary and otherwise.