Part 2: A Victory for Climate Security 2036

Backcasting as a methodology for seeing into the future

It’s hardly scientific, but backcasting as a strategic planning tool can be instructive in seeing new paths forward and where the current path is stuck. Part 2 of our paper (linked in it entirety here as a PDF) examines the four ways we looked at the challenge of transitioning BP toward its stated goal of being an integrated energy company — using fiduciary money as the financing partner/steward that releases BP from its short-term obligations to speculators. As a reminder, the exercise is pinned to a future where this kind of news story (more readable here) can be published.

Part 1

Part 3

News from future

Part 2: Backcasting as a methodology for seeing into the future

A Victory for Climate Security Datelined 2036

“People who cling to paradigms… take one look at the spacious possibility that everything they think is guaranteed to be nonsense and pedal rapidly in the opposite direction. But… everyone who has managed to entertain [the notion or experience that there is no certainty in any worldview], for a moment or for a lifetime, has found it to be the basis for radical empowerment.”

Rather than fearing how the climate crisis is resolved because it’s uncertain, we have an invitation to explore other ways to get there – rather than what is on offer. One of the greatest failings of environmental sustainability, as practiced, is its lack of a catalyzing and galvanizing endpoint when the options seem rich. Anything is possible when nothing is certain. Accepting that mobilizes the power to change paths toward a livable future when we are, instead, mired in the sacrifices we are asked to make to tread water where we are. We can envision something better. That much is certain.

Because it’s unscientific, and we don’t pretend that it is, backcasting is a tough sell to skeptics who want certainty that Step A will outperform Step B by X% when no such certainty can be guaranteed. Instead, backcasting contrasts the status quo with a desired and unambiguous alternative and highlights a strategic path to get there.

Assumptions

Our exploration requires some assumptions that are written in past tense. We:

Rather than asking “How do we do it?”, we time travel in Exhibit 1 to explain “How we did it.” You might have different assumptions. This is, after all, an imagination initiative.

Of course, BP’s situation is part of a much larger social-structural issue, identified by us, that is included in our background considerations and informs our “educated guesswork” but is not outlined specifically in this paper.

Reach out to ian@bankofnature.eco if you want to explore some of the larger assumptions that inform our conclusions in this paper.

Brainstorm Framework

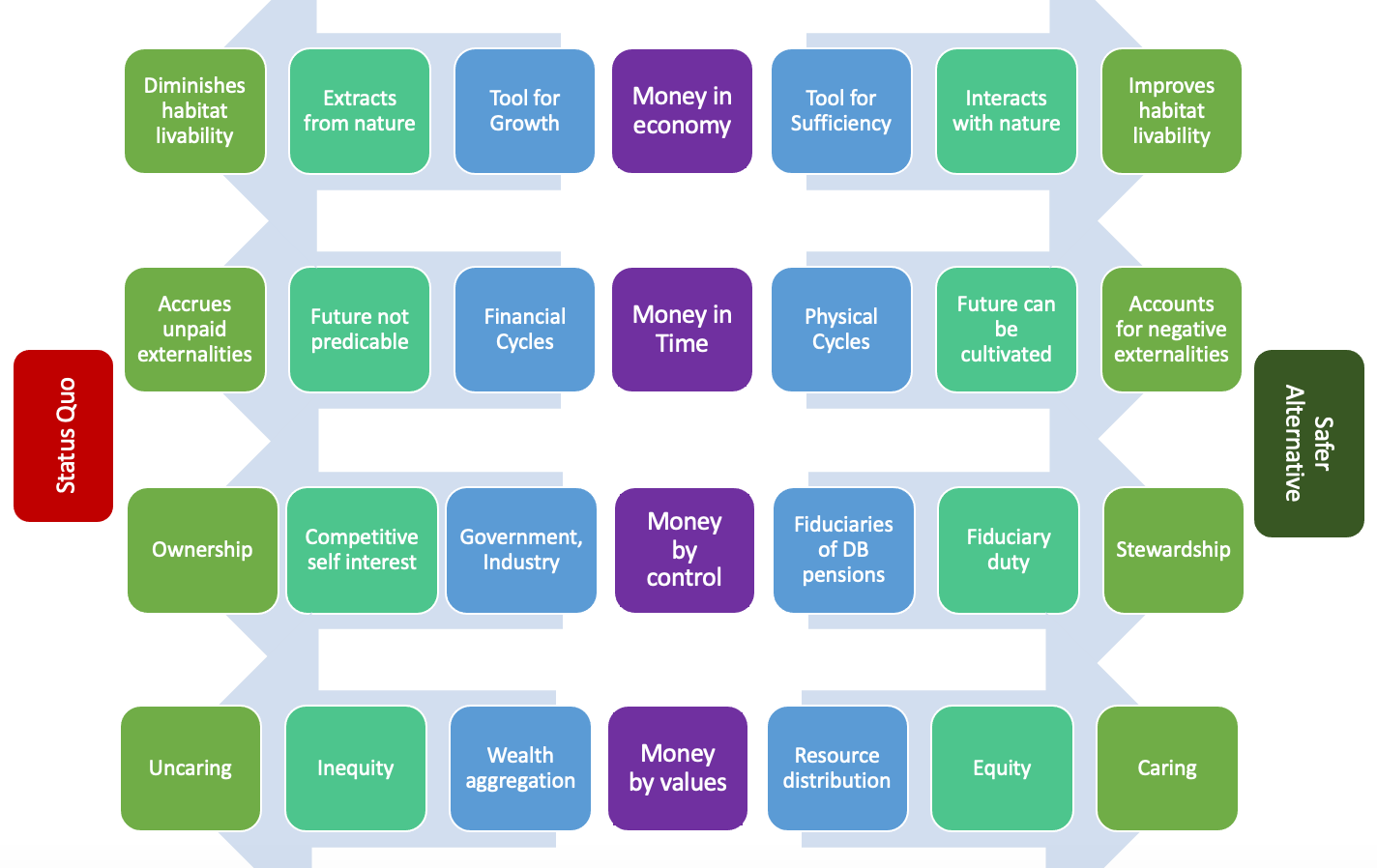

Secondly, our methodology involves a brainstorm structure. Again, your approach might be different. For discussion, this is how you might look at the backcasting challenge.

Driving and Restraining Forces

Thirdly, in our methodology, we have recognized that there are constants that exist now and will persist in our desired future. They drive toward your goal or restrain your goal. Accepting what won’t change, but can be made to work in your favor, is another way to animate your new path.

For example, money. We agree, as a society, that one slip of paper is more valuable, and buys four US gallons of BP/Amoco gas at the pump, than an identical slip of paper -- except for the number stamped on it – that buys only one gallon of BP/Amoco gas. It’s a social agreement and an essential tool in how we move through society.

Humans in society are specialists in skills that might not meet all their essential needs. They will require money to procure the needs they don’t have otherwise. You can do the same analysis with time, consumer demand, trust, and other constants that can be used to drive, rather than, restrain your desired outcome.

Action Planning

A fourth component of our methodology is to theorize an action plan inspired by it. It’s instructive methodology to consider what actions realize your desired outcome.

For instance, we want the arrows in the illustration above to move right toward a “safer alternative” but the status quo has society firmly to the left. A major takeaway in our version of this exercise has been the evaluation of “money in control” which led to our ideas about societal structures and money as a vital, critical social decision maker.

With tens of trillions in financial holdings, fiduciaries of defined benefits plans control more money, in the aggregate, than any one nation state or industry by many multiples. How and why that money moves has profound consequence to the shape of the global economy. Yet, fiduciaries don’t show up as powerbrokers in our society structure. They are coopted by the larger nonfiduciary finance world. As a consequence, fiduciaries are not, in general, doing the job they are supposed to be doing.

This is a breach of duty to the young beneficiary not yet age-eligible to collect for decades – who is a proxy for all eight billion of us. Fiduciary money is that big.

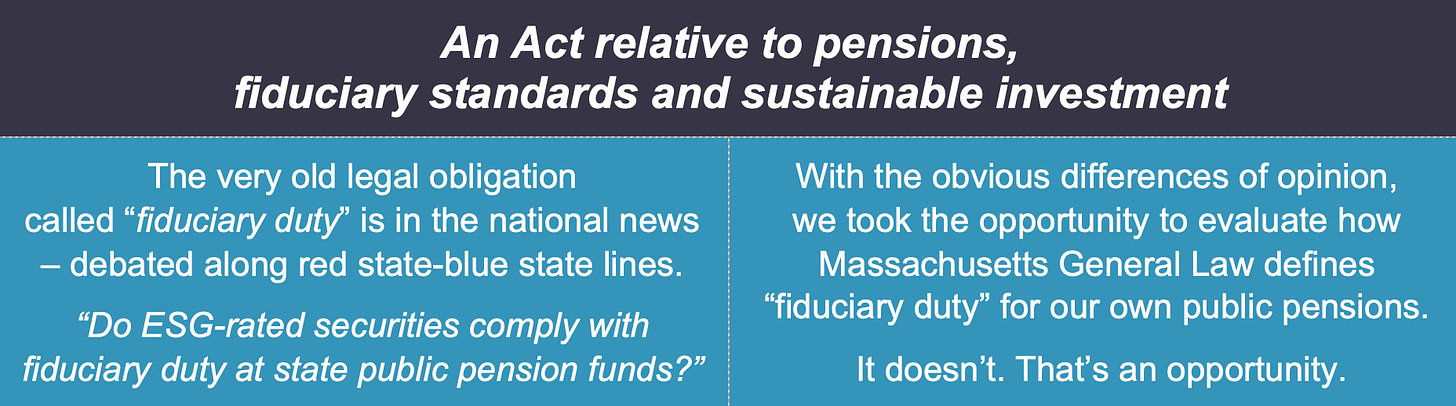

That’s information that has inspired a real world initiative: our Fiduciary Standards Legislation presently in debate in the Massachusetts Senate. This bill, which lands in the middle of a US partisan debate about fiduciary duty and ESG investing among public pensions, seeks to clarify the purpose of a public pension in Massachusetts and provide a model for fiduciaries everywhere. This is the money that helps BP sidestep the limitations of the status quo.