Introduction

According to the current cosmological model, so-called ‘dark matter’ accounts for about 85 percent of the mass of the universe. I recently learned about a form of money in our economy that calls to mind this form of matter—and no, it’s not dark money, that untraceable variety of political financing. It’s pension money. Pension money is so huge, I learned, that it has the power to change the world.

To find out how and why, I interviewed Ian Edwards and Tim MacDonald, founders of Bank of Nature. Bank of Nature is not a ‘bank’ in the conventional sense but a thought leader and advocacy organization for a new stewardship model of the world’s financial system—a model that is future-thinking rather than myopic. Bank of Nature could, at some point, itself become a channel for stewardship funds for future-driven opportunities. Yet its initial challenge is to convince pension administrators to stop investing in whatever stocks are in front of their noses, and turn instead to investing in forever, which is what Ian and Tim argue they should have been doing all along.

Interview

FDMS: Most of us don’t think about pensions, if we have them. Should we? If so, why?

IE: Yes, we should pay attention to pensions—certainly in ways that don't happen in the status quo.

Specifically, defined-benefits pensions[1] have an enormous financial scale. They are guided by a narrow legal scope called ‘fiduciary duty’ that has such wonderfully human-scale priorities as the Duty of Loyalty, Duty of Care and Duty of Impartiality. Pensions are legally bound to comply with those ideals. Whether pensions actually comply is the subject of our Bank of Nature initiative—and, spoiler, they don't. Furthermore, pensions are pinned vividly to a future promise many decades out. There is no better example of longtermism in the economy than a pension. They are built to be immortal.

The work of a pension fiduciary is to ensure that the pension’s money is used to deliver a dignified future. How pension money moves in the economy is the single greatest influence over economic health and the quality of our future. Being so large and consequential, pensions need serious scrutiny because, as we argue, they are not working as designed.

If you consider only the climate, which is a crisis currently lacking remedies at scale, we should all care about pensions because they control money with the mission, the duty and the volume to pay for climate security. They don’t. It's a missed opportunity. They have the financial power to lead us through a just energy transition if we point them in that direction: not only for their own retirees but also for the world.

FDMS: How big a deal are pensions, financially?

IE: According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, all types of retirement savings worldwide control $50 trillion to $60 trillion, which is money at the scale of the climate crisis. The type of pension that we focus on, defined-benefits plans, which are protected by fiduciary duties, have the most immediate powers to overcome that crisis. Defined-benefits plans are about half of that global value: $25 trillion to $30 trillion, or 12% to 15% of the global money supply. So, a big deal.

FDMS: What is a pension’s ‘fiduciary duty’ to manage its assets? Do pensions today meet the standard? If not, why not?

IE: In modern lingo, a pension is an asset owner. But pensions don’t actually own their assets: they steward them. This distinction has profound implications for the way fiduciaries use their vast pension principals to fulfill their fiduciary duty.

A pension fiduciary, in particular, has a duty to people who are owed a dignified future. Most commonly, that’s called income security, but it doesn't capture the full scope of a fiduciary’s obligations.

What is forgotten in common fiduciary practice is not whether the fiduciary of a pension plan must make money but how that money is made. If chasing maximized financial returns in the financial markets diminishes our future, socially and environmentally, then that does not fulfill fiduciary duty. Fiduciaries are not exercising the required ‘plenary powers of discretionary authority’—especially to today’s youngest new hires who are recruited, in part, by the promise of future retirement security.

Over the past fifty years, lax fiduciary regulations have caused pensions to lose sight of their purpose, which is not only to deliver a rate of return but also to safeguard the future. Our Bank of Nature initiative exists to help them to find their way back to it.

FDMS: So a ‘dignified future’ for pension plan recipients, then, would essentially become a dignified future for everybody, is that correct?

IE: Exactly. The pension obligation to deliver a dignified future is backed by tens of trillions of dollars, globally. So, if pensions address, for example, climate security for the relatively few pension participants, they will move enough money to deliver a dignified future for eight billion.

FDMS: Pensions invest in the stock market. Has this always been the case? If not, how did it come about?

IE: Before 1972, pensions were not significant participants in the stock market because of the legal interpretations of ‘prudence’—defined as the reasonable actions of reasonable people. A foundational idea in fiduciary law is the ‘prudent person’.

Speculative Wall Street-style exchanges were considered imprudent and therefore illegal for fiduciary purposes. Fiduciaries, instead, were limited to lending money, for example, to governments and real estate.

TMD: Then, in 1969, the Ford Foundation commissioned two New York lawyers, William Cary and Craig Bright, to advise them whether the law of fiduciary duty really did prevent trust fiduciaries (specifically university endowments) from participating in the stock markets.

Messrs Cary and Bright advised, correctly, that it does not. In 1972, the National Commission on Uniform State Laws put Messrs Cary and Bright’s advice into law, through the Uniform Management of Institutional Funds Act.

Over the next decade or so, first university endowments, then charitable foundations, then company pensions, and finally public and union pensions began moving money into the stock markets, as a new ‘lore of the prudent investor’ pushed the ‘prudent person’ out of accepted practice.

IE: The law didn't change, but how we interpret the law (or the lore) changed.

Since then, pensions have been called ‘institutional investors’ with the same latitude as any ‘reasonable person making reasonable choices’. This means that pensions can gamble in the stock market, bankroll new forms of investing, such as leveraged buyouts and private equity, and amplify extractive industries, such as oil and gas, because these stocks offered high returns, regardless of the long term effects.

Our Bank of Nature initiative makes the case that the 1969 interpretation of fiduciary prudence opened a Pandora’s box. Now, with more than fifty years of lived experience behind us, it is clear that pensions are breaching their fundamental duties of care, loyalty and impartiality by chasing the risks and returns of Wall Street.

We don't need to roll back the clock to the era of government bonds, but we do need to take a hard look at the use of fiduciary money for non-fiduciary purposes, and the very real negative fallout from that.

FDMS: Stock-market investment implies an exit strategy of some kind, such as ‘buy low, sell high’. If pensions are essentially immortal, do they need an exit strategy?

TMD: Unlike bonds, which have a maturity date on which they are repaid, stocks have no maturity date. They just keep going. So trading in equity shares becomes about capturing growth in the selling price, which is speculative. Speculation on growth is what drives buying, which empowers selling, thereby sustaining liquidity in the stock markets.

What Wall Street does, by evolutionary design, is to mediate the tension between serving investors’ opportunistic needs for profit and enterprise’s needs for longevity at scale in its financings.

What results is the buy-and-hold relay race of corporate equity, with people buying when they have money to sell, in increments that they have available, holding for a time, and then selling when they want money back to spend on something real in the physical economy.

Enter pensions, which are large, programmatic and evergreen. As investors they need longevity at scale. But the markets only offer liquidity in increments.

It is not a good fit.

When pension money enters the markets, it never needs to come out. There is never a need to sell. All that money sitting in the markets not trading would impair the markets’ ability to deliver liquidity. So pension money has to become pure speculation, selling to extract a profit opportunistically, and using the proceeds of every sale to buy something else. Buy-and-hold becomes buy-low-to-sell-high, which becomes buy-high-to-sell-higher.

The economy booms, until it goes bust.

FDMS: How does this happen?

TMD: To answer that question, let’s imagine an individual—we’ll call him Bob—who has accumulated a certain amount of wealth beyond what he needs to maintain his daily lifestyle.

The wisdom of Bob is that “I buy when I have some money that I can afford to lose: I call it mad money. I sell when I need that money back, to spend on something in my life: a home, college for the kids, the kid’s wedding, my yacht, a vacation for a major wedding anniversary. Big stuff, ya’ know. Sure, I move my money around a bit, to try and make sure I am in the best stocks, but mostly, once I buy, I just hold it. I have better things to do with my time than get jerked around by the ticker tape.”

Between 1929 and 1972, this pretty much was the stock market: a market for Bob.

During that roughly 40-year period, a powerful social innovation took shape: the workplace pension. First governments, then unions, and eventually non-union enterprises added a pension promise to their compensation programs to attract and retain good workers.

This became a cornerstone of the mid-century American dream: a house in the suburbs, a car in the driveway, and a good job with a good pension.

A workplace pension is a mutual aid society that uses actuarial science to average the cost of supplying an income in retirement to workers after they stop working, averaging across large populations of statistically similar workers.

Money set aside for pensions aggregated over time into trusts established to hold the money, keep it safe, and use it to make contractually calculated regular payments to qualified recipients until they died.

This money could be put to work to make more money to pay administrative costs and, if the numbers were right, to cover substantial portions of the contractually calculated payouts to retirees. I call this the fiduciary cost of money.

The evidentiary standard of prudence and loyalty under the law of fiduciary duty has always been the ‘common sense’ of ‘reasonable people’ of relevant knowledge and experience. In managing trusts, such as for an inheritance, questions historically arose about what constitutes a ‘safe’ investment. To answer this question, courts sidestepped the complexities of fact-finding by following a court-made rule limiting trustees to investments comprising loans to governments or against real estate. This became known as the ‘Lore of the Legal List’, which essentially was a gloss over the law of fiduciary duty. It was incorporated into custom and usage by pension trustees during the 20th century, keeping pension money for all intents and purposes out of the stock markets, which remained dominated by Bob.

During the middle of the 20th century, money continued to pile up inside those trusts until the amounts set aside for dignified retirement became truly vast. Then, as we explained earlier, the ‘lore of the legal list’ was replaced in the 1970s by the ‘lore of the prudent investor’.

One might think that Bob would be the paradigm of the prudent investor, but one would be wrong.

The prudent investor is actually the prudent professional investor: paid professional portfolio managers, commonly known today as asset managers.

Bob is a buy-and-hold investor. A pension is not like Bob. It comes into money as its population of workers grows, but it never really needs that money back. Bob, like all of us, exists for a while, then he is gone. A pension trust is forever.

With all that forever money going into the markets, designed as they are for liquidity, pensions needed a reason to sell, even though they didn’t actually need to sell. That reason is opportunistic profit-taking, and its corollary, loss-avoidance. An asset manager thus buys when the price is low, and sells when the price goes high, or when it becomes apparent that they ‘missed the market’ and the price is not going to rise further or may fall. ‘Prudence’ then becomes a matter of timing, and of riding short-term volatility in share prices within the larger expectation of price increases in the long term.

As more and more forever money comes under the control of asset managers, the frequency of buy-low-sell-high opportunities vectors toward zero. But the markets must remain liquid, which means that asset managers must trade. So, over time, ‘buy-low-to-sell-high’ becomes ‘buy-high-to-sell-higher’.

The primary driver of share price growth then becomes inflation in share valuation relative to earnings, supported by corporate giantism and stock buybacks. This inflation also inflates the collateral value of non-financial assets, which in turn expands the borrowing capacities of pretty much everyone. Lending against this inflated value creates a credit bubble.

Yet unlike equity, debt has to be repaid. Credit bubbles always eventually burst when borrowers who borrowed against manufactured liquidity in the stock market find themselves without sufficient cash to pay back those borrowings. Bursting credit bubbles then also burst stock-market pricing bubbles, sometimes with catastrophic consequences. Witness: 2008. Also, 1929: a stock market bubble fueled by bank deposits lent to the stock market. And, further back, 1907: a stock market bubble fueled by life insurance premiums.

FDMS: So would the stock market be better off as a whole without pension funds in it?

TMD: To answer this question, we need to distinguish between ‘ownership equity’ and ‘stewardship equity’.

The stock market was designed to trade in shares of ownership equity. Any actor seeking liquidity can participate in the stock market by owning equity—that is, equal shares, as defined earlier.

Ownership equity is inherently extractive. As traded in the stock market, it externalizes costs, losses and risks to maximize price and profit. Ownership equity for Bob is a buy-and-hold intergenerational relay race where everybody gets their bit, in turn. Ownership equity for an asset manager is a zero-sum game of winners and losers maximizing pecuniary, risk-adjusted returns on growth in the financial interests of their beneficiaries, and themselves.

Pensions and endowments are a form of what we call stewardship equity. Whereas ownership equity needs a selling price, stewardship equity needs recurring cashflow. Stewardship equity is inherently supportive. It is a better fit for pensions, because it can supply money to the right enterprises in the right way, in turn shaping the right technologies for the right economy and a cohesive society. It can keep this investment going into perpetuity for a future quality of life, for some directly, and for us all, consequently.

Stewardship equity is deployed by fiduciary financiers through equity paybacks to a fiduciary cost of money, plus an opportunistic upside. The paybacks come from enterprise cashflows prioritized for suitability, longevity and fairness.

By ‘suitability’ I mean the suitability of a technology to its times. By ‘longevity’ I mean the longevity of the social contract with popular choice.

By ‘fairness’ I mean fairness across six vectors of enterprise cash flows:

Fairness to suppliers (Fair Trade);

Fairness to communities (Fair Engagement);

Fairness to nature and society (Fair Reckoning);

Fairness to workers (Fair Working);

Fairness to customers and competitors (Fair Dealing); and

Fairness to the savers whose savings are the ultimate source of the money (Fair Sharing).

The rubrics of suitability, longevity and fairness create a framework for prudent stewardship and accountability to our shared common sense of what is properly careful (prudent) and caring (loyal) that is not possible with ownership equity in the markets.

Assuming pensions make the transition away from ownership equity in the markets toward stewardship equity through direct negotiation with enterprises, it is possible to imagine that there will be times when pensions have money sitting idle, waiting for stewardship equity opportunities to arise. In those situations, pensions may find it prudent and loyal to ‘park’ that money in the markets until it is needed for stewardship.

Returning market participation to those who need liquidity will return the markets to what they were designed for, and will eliminate the systemic risks arising from the mismatch between pensions’ requirement for longevity and the markets’ requirement for liquidity.

FDMS: How does stewardship equity work in practice? Can you describe an example? Who are the actors, how do they interact, and what is the outcome?

TMD: Stewardship equity is the proven, reliable payback structure commonly used for real estate equity. I learned it doing tax credit partnerships in affordable housing and renewable energy. It uses a limited liability company as the legal form of ownership and control.

For example, let’s imagine how stewardship equity would be used to finance a utility-scale solar array. This type of project typically involves several kinds of cashflow: land rents, design costs, construction and maintenance costs, a power purchase agreement (PPA) with the local utility to take the power onto the grid, and—critically—the cost of financial capital.

Assuming the project developer is a public company, it will finance its development costs through the capital markets. Construction will commonly be financed with debt at 100% of approved costs, against a commitment to take out the debt from equity sources. In the stewardship equity model, the source of equity would be a consortium of pensions and endowments.

Revenue from the sale of energy under the PPA would pay project costs in the following order of priority:

Contractually approved costs of doing business—site, permits, technology, payroll, and so on—arriving at free cash flow from ongoing operations;

Debt service on prudent debt, arriving at free cash flow to equity;

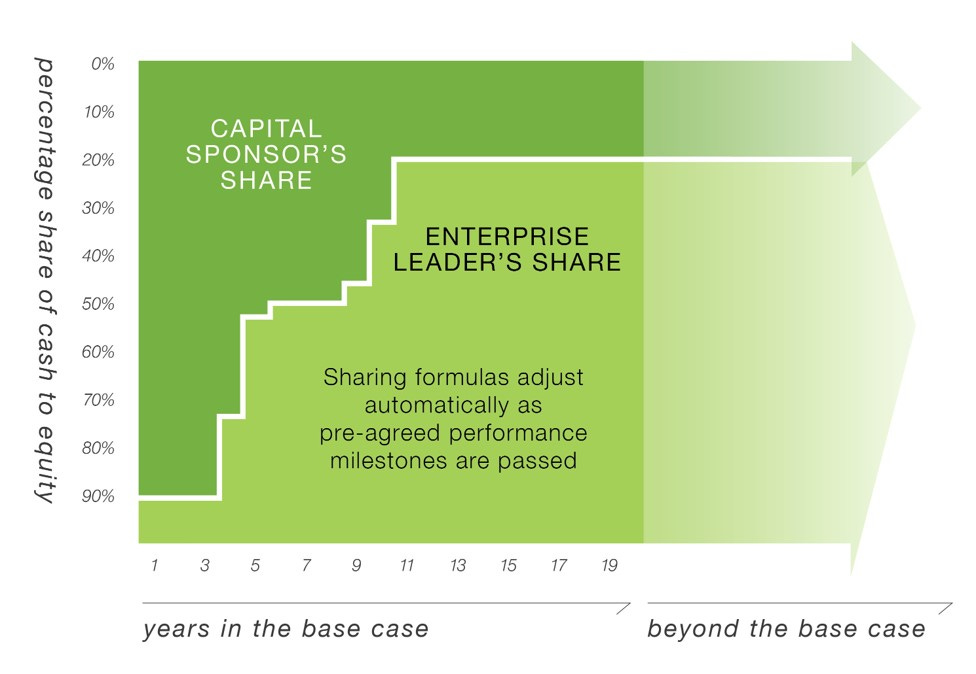

Repayment on stewardship equity according to the following schedule:

A percentage sweep to stewardship equity—say, 90%—until aggregated repayments equal the original amount advanced;

Subsequently, a lower percentage to stewardship equity—say, 80%—until an actuarial cost of money is realized;

Thereafter, a ratable sharing of maybe 20% for as long as the solar array sells power to the grid, or until parties agree to a negotiated buyout.

Negative covenants in the operating agreement would hold the managing member committee to the original business plan and operating budget, unless the investor members agreed by vote on changes.

FDMS: Would stewardship equity invest only in commercial projects with a known rate of return or could it invest in whole businesses? Could it invest in mission-driven enterprises or social enterprises? What are stewardship equity’s selection criteria?

TMD: The limiting factor is prudence. The enterprise would have to generate a cashflow. Pension money tends to be pretty conservative, so pension-funded stewardship equity would tend to gravitate toward mature technologies or mature companies: those near the top of the S-curve in the diagram above.

Mature, publicly-traded companies wanting to get out of Wall Street would be prime candidates for pension-funded acquisition for stewardship equity.

In fact, US public pensions alone have more than enough funds to buy out the world’s top ten oil and gas firms at current valuations, private equity-style. Pensions could then place these companies into prudent stewardship through equity paybacks, real estate equity-style. The companies would be steered toward becoming positive contributors to the reconstruction of our global energy system for energy sufficiency, habitat longevity and social equity, NASA moonshot-style.

What applies to the energy system applies also to other critical economic systems.

FDMS: How do we get pensions out of the financial markets and into stewardship equity? Persuasion, legislation, public pressure, or all of these and more?

TMD: Although the law of fiduciary duty looks to our common sense as the evidentiary standard of prudence and loyalty, our common sense has surrendered accountability to the prudent professional investor, who tells pensions that the markets are their only choice, and that it is their fiduciary duty to extract and externalize in those markets.

We have to cancel that belief and retake control of pensions and endowments, by restating and upgrading our common knowledge of their purpose, powers and accountability.

Once our common sense begins mandating the move out of ownership equity into stewardship equity, most pension fiduciaries will follow. There will be resistance from market professionals, and we may need litigation or even legislation to help overcome that resistance.

But we will not get legislation or win litigation if we do not first update and upgrade our shared common sense.

This initial change is a cognitive shift, but I am not sure it can begin with the fiduciaries. All innovations start in civil society as a collection of institutions and actors who curate knowledge and new learning to evolve our shared social narrative. It is within this knowledge and learning that the cognitive shift has to happen first. How, exactly, to initiate that shift is the focus of our efforts in Bank of Nature.

FDMS: If substantially all of the pension money floating around the global economy made direct investments in stewardship ventures, how would it change the world, and how quickly? How different might society and the planet look by 2050 or 2100?

TMD: Today, pension money in the markets accelerates the pace of trading. This drives concentrations of wealth and power, triggering a cascade of social failings:

Short-termism

Market elitism

Corporate gigantism

Financial system instability

Social safety net insecurity

Cultural and ecological unsustainability

Dark-money capture of politics and public discourse

Political divisiveness degenerating toward violence

Failure of society to hold institutions accountable for the exercise of their powers true to their purposes.

Pulling pensions out of ownership equity in the markets and putting them into stewardship equity in the real, physical economy will correct these failings. It will also recover the fiduciary cost of money, which ownership equity in the markets cannot do. Most significantly, it releases a huge supply of funds to enterprises focused on long-term solutions, such as “transitioning away from fossil fuels in a just, orderly and equitable manner,” to quote COP28.

Under a stewardship equity model, a pension trust is able to keep going as a forever machine, recovering its fiduciary cost of money and honoring a forever promise to a forever population of current and future workers.

Deploying tens of trillions of dollars in this way would have significant effects:

The climate crisis would be resolved, as described earlier, along with other similar crises.

Exotic features of the market—portfolios of consumer debt, derivatives, hedge funds, hostile takeovers, share buyback, corporate gigantism, predatory private equity, etc.—that depend on controlling pension money will go away.

The stock market will shrink in size and be returned to the individual investor for the purpose of providing risky capital to high-growth innovations.

Credit will shrink as inflated collateral values deflate to their right size. Banking will cease to be a fee-driven product provider to the markets and will return instead to being a service provider to the economy and society.

Dark Money will be substantially defunded.

Social cohesion will be restored as concentrations of wealth and power will be reversed, dissipating through a broad swath of the population.

Popular participation in prudent stewardship through fiduciary finance and equity paybacks will become a powerful new point of citizen engagement and institutional accountability.

Let’s imagine what else!

Conclusion

Understanding the sheer scale of pension money has been an eye-opener for me, and hopefully also for anyone else reading this interview. It calls to mind another form of directed investment, sovereign money, which I discussed in my book, A Planetary Economy.[2] Sovereign money is the creation of new money by government, put to work through government programs. Money spent by government on such initiatives as decarbonizing the economy, ecological restoration, or basic income, would circulate through the economy as production and consumption, eventually being mopped up via taxation.

The idea was the brainchild of Joseph Huber and James Robertson,[3] who argued that governments are under no obligation to create new money through banking debt, as they do now. A beneficial side-effect of sovereign money would be reform of the banking system, and with it, the financial markets, in ways similar to what Tim described.

In the book, I highlighted sovereign money as a powerful mechanism to steer the economy toward alignment with nature, at the same time broadening the economy’s basis of prosperity, a necessary prerequisite to planetary alignment. But that book missed pension money altogether, perhaps because, like dark matter, it is hidden—albeit hiding in plain sight—or its scale underappreciated.

Pension money in the form of stewardship equity is possibly even more powerful than sovereign money. Not only does it circulate at a comparable scale but it has another advantage, which is that it is not beholden to the whims of political legislatures. If pension funds can be convinced to explore this new direction, they wouldn’t need legislation to proceed. They can just act. Mission-driven investment on a planetary scale could emerge first through private-sector pension money, long before the public sector acts. To-date, the vox populi has achieved little in trying to convince intransigent or divided legislatures to do any more than fiddle around the edges of today’s giant, planetary problems. Perhaps those calling for systemic change are talking to the wrong people?

Ian and Tim highlighted the power of pension money to improve the lives of all, including the majority who are not pension recipients. Yet pensions are only one part of a person’s life story, the part that begins in middle or later life. As I argued in A Planetary Economy, a major contributor to a future widespread prosperity will be basic income, earned from birth and paid throughout adulthood. It need not be funded through income taxes or wealth taxes, although they are options. Other mechanisms include sovereign money, as well as ‘common capacity fees’—small fees paid by corporations for the use of common capacity, such as the electric grid, the atmosphere, or the financial system. Into this portfolio we can add pension money or other fiduciary money for stewardship equity. Returns from this equity could fund basic income, thereby indirectly providing a form of pension benefit to all, particularly during the early stages of life when people most need it.

As Tim describes, the first and most important shift will be a cognitive one. In Western thought, it is a shift from what Kenneth Boulding called the ‘cowboy economy’ of the 19th century to the ‘spaceman economy’ of the late 20th.[4] I can think of no better conclusion than to allow Tim to express it in his own words.

TMD: In the 19th century, the West experienced nature as vast, and we as not. Our lived experience was that we could always take and take from nature without ever reckoning with the consequences because those consequences would always just disappear into an infinite geobiophysical frontier.

By the early decades of the 20th century, that frontier was gone. Everywhere the West went, we were already there. Nature was still vast, but so, now, were we.

During the 20th century, we first tried global warfare at an industrial scale as a adaptation strategy. Then we looked to space. On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong took his historic “one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind,” but the step he took was not the leap we were expecting. We ventured into space expecting to find a new frontier for continued infinite expansion. When we got there, all we found were rocks. No air to breathe. No water to drink. No life to live.

The step Neil took was not a leap into a new frontier. It was a leap into a new reality. Earth is all we have. We have to take care of it, because it is our home.

In the early decades of the 21st century we are confronting the new reality Ian articulated: that nature is a bank. Climate change is an eviction notice.

When we take money from a bank, the withdrawal comes with terms attached, and with legal consequences if those terms are not honored. Just the same way, when we take from nature there are terms and consequences, according to the laws of nature.

Our challenge for stewardship in the 21st century is to teach ourselves how to honor the terms that nature imposes upon our interactions with it and with each other.

Works Cited

Boulding, K. E. (1966) The economics of the coming Spaceship Earth. In Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy, edited by H. Jarrett (pp. 3–14). John Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD.

Huber, J. and Robertson, J. (2000) Creating New Money: A Monetary Reform for the Information Age. Report of the New Economics Foundation, London.

Murison Smith, F.D. (2020) A Planetary Economy. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

[1] Defined-benefits pensions pay a fixed amount upon retirement, based on a retiree’s earnings, age and tenure, among other factors. They are most common in the public sector. Employee stock-ownership plans, profit-sharing plans, and 401(k)s are examples of defined contribution plans, which do not pay a fixed amount but which instead grow a lump sum from employee and employer contributions. 401(k)s are usually invested in the financial markets, and therefore subject to its ups and downs.

[2] Murison Smith (2020).

[3] Huber and Robertson (2000).

[4] The ‘cowboy economy’ and ‘spaceman economy’ were concepts created by the economist Kenneth Boulding in the 1960s: see Boulding (1966).